Muslims are the fastest-growing religious group in the world. The growth and regional migration of Muslims, combined with the ongoing impact of the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS) and other extremist groups that commit acts of violence in the name of Islam, have brought Muslims and the Islamic faith to the forefront of the political debate in many countries. Yet many facts about Muslims are not well known in some of these places, and most Americans – who live in a country with a relatively small Muslim population – say they know little or nothing about Islam.

Here are answers to some key questions about Muslims, compiled from several Pew Research Center reports published in recent years:

How many Muslims are there? Where do they live?

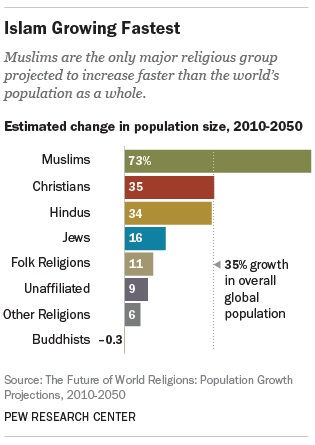

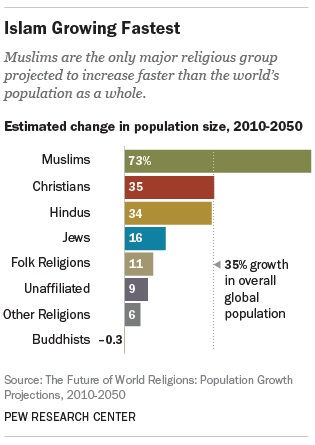

There were 1.6 billion Muslims in the world as of 2010 – roughly 23% of the global population – according to a Pew Research Center estimate. But while Islam is currently the world’s second-largest religion (after Christianity), it is the fastest-growing major religion. Indeed, if current demographic trends continue, the number of Muslims is expected to exceed the number of Christians by the end of this century.

There were 1.6 billion Muslims in the world as of 2010 – roughly 23% of the global population – according to a Pew Research Center estimate. But while Islam is currently the world’s second-largest religion (after Christianity), it is the fastest-growing major religion. Indeed, if current demographic trends continue, the number of Muslims is expected to exceed the number of Christians by the end of this century.

Although many countries in the Middle East-North Africa region, where the religion originated in the seventh century, are heavily Muslim, the region is home to only about 20% of the world’s Muslims. A majority of the Muslims globally (62%) live in the Asia-Pacific region, including large populations in Indonesia, India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Iran and Turkey.

Indonesia is currently the country with the world’s single largest Muslim population, but Pew Research Center projects that India will have that distinction by the year 2050 (while remaining a majority Hindu country), with more than 300 million Muslims.

The Muslim population in Europe also is growing; we project 10% of all Europeans will be Muslims by 2050.

How many Muslims are there in the United States?

According to our best estimate, Muslims make up just less than 1% of the U.S. adult population. Pew Research Center’s 2014 Religious Landscape Study (conducted in English and Spanish) found that 0.9% of U.S. adults identify as Muslims. A 2011 survey of Muslim Americans, which was conducted in English as well as Arabic, Farsi and Urdu, estimated that there were 1.8 million Muslim adults (and 2.75 million Muslims of all ages) in the country. That survey also found that a majority of U.S. Muslims (63%) are immigrants.

Our demographic projections estimate that Muslims will make up 2.1% of the U.S. population by the year 2050, surpassing people who identify as Jewish on the basis of religion as the second-largest faith group in the country (not including people who say they have no religion).

A recent Pew Research Center report estimated that the Muslim share of immigrants granted permanent residency status (green cards) increased from about 5% in 1992 to roughly 10% in 2012, representing about 100,000 immigrants in that year.

Why is the global Muslim population growing?

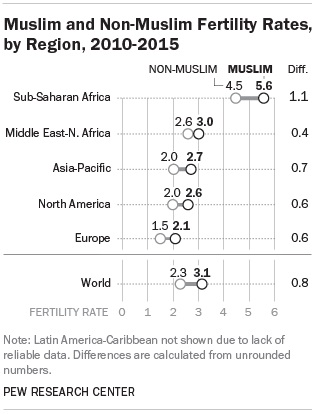

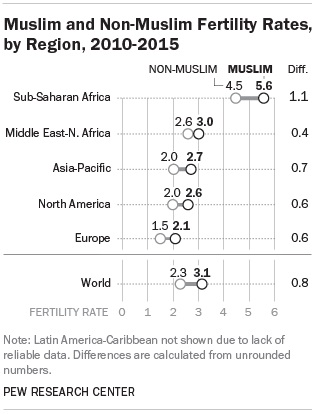

There are two major factors behind the rapid projected growth of Islam, and both involve simple demographics. For one, Muslims have more children than members of other religious groups. Around the world, each Muslim woman has an average of 3.1 children, compared with 2.3 for all other groups combined.

There are two major factors behind the rapid projected growth of Islam, and both involve simple demographics. For one, Muslims have more children than members of other religious groups. Around the world, each Muslim woman has an average of 3.1 children, compared with 2.3 for all other groups combined.

Muslims are also the youngest (median age of 23 years old in 2010) of all major religious groups, seven years younger than the median age of non-Muslims. As a result, a larger share of Muslims already are, or will soon be, at the point in their lives when they begin having children. This, combined with high fertility rates, will fuel Muslim population growth.

While it does not change the global population, migration is helping to increase the Muslim population in some regions, including North America and Europe.

What do Muslims around the world believe?

Like any religious group, the religious beliefs and practices of Muslims vary depending on many factors, including where in the world they live. But Muslims around the world are almost universally united by a belief in one God and the Prophet Muhammad, and the practice of certain religious rituals, such as fasting during Ramadan, is widespread.

In other areas, however, there is less unity. For instance, a Pew Research Center survey of Muslims in 39 countries asked Muslims whether they want sharia law, a legal code based on the Quran and other Islamic scripture, to be the official law of the land in their country. Responses on this question vary widely. Nearly all Muslims in Afghanistan (99%) and most in Iraq (91%) and Pakistan (84%) support sharia law as official law. But in some other countries, especially in Eastern Europe and Central Asia – including Turkey (12%), Kazakhstan (10%) and Azerbaijan (8%) – relatively few favor the implementation of sharia law.

How do Muslims feel about groups like ISIS?

Recent surveys show that most people in several countries with significant Muslim populations have an unfavorable view of ISIS, including virtually all respondents in Lebanon and 94% in Jordan. Relatively small shares say they see ISIS favorably. In some countries, considerable portions of the population do not offer an opinion about ISIS, including a majority (62%) of Pakistanis.

Favorable views of ISIS are somewhat higher in Nigeria (14%) than most other nations. Among Nigerian Muslims, 20% say they see ISIS favorably (compared with 7% of Nigerian Christians). The Nigerian militant group Boko Haram, which has been conducting a terrorist campaign in the country for years, has sworn allegiance to ISIS.

More generally, Muslims mostly say that suicide bombings and other forms of violence against civilians in the name of Islam are rarely or never justified, including 92% in Indonesia and 91% in Iraq. In the United States, a 2011 survey found that 86% of Muslims say that such tactics are rarely or never justified. An additional 7% say suicide bombings are sometimes justified and 1% say they are often justified in these circumstances.

In a few countries, a quarter or more of Muslims say that these acts of violence are at least sometimes justified, including 40% in the Palestinian territories, 39% in Afghanistan, 29% in Egypt and 26% in Bangladesh.

In many cases, people in countries with large Muslim populations are as concerned as Western nations about the threat of Islamic extremism, and have become increasingly concerned in recent years. About two-thirds of people in Nigeria (68%) and Lebanon (67%) said earlier this year they are very concerned about Islamic extremism in their country, both up significantly since 2013.

What do American Muslims believe?

Our 2011 survey of Muslim Americans found that roughly half of U.S. Muslims (48%) say their own religious leaders have not done enough to speak out against Islamic extremists.

Living in a religiously pluralistic society, Muslim Americans are more likely than Muslims in many other nations to have many non-Muslim friends. Only about half (48%) of U.S. Muslims say all or most of their close friends are also Muslims, compared with a global median of 95% in the 39 countries we surveyed.

Roughly seven-in-ten U.S. Muslims (69%) say religion is very important in their lives. Virtually all (96%) say they believe in God, nearly two-thirds (65%) report praying at least daily and nearly half (47%) say they attend religious services at least weekly. By all of these traditional measures, Muslims in the U.S. are roughly as religious as U.S. Christians, although they are less religious than Muslims in many other nations.

When it comes to political and social views, Muslims are far more likely to identify with or lean toward the Democratic Party (70%) than the Republican Party (11%) and to say they prefer a bigger government providing more services (68%) over a smaller government providing fewer services (21%). As of 2011, U.S. Muslims were somewhat split between those who said homosexuality should be accepted by society (39%) and those who said it should be discouraged (45%), although the group had grown considerably more accepting of homosexuality since a similar survey was conducted in 2007.

What is the difference between Shia Muslims and Sunni Muslims?

Sunnis and Shias are two subgroups of Islam, just as Catholics and Protestants are two subgroups within Christianity. The Sunni-Shia divide is nearly 1,400 years old, dating back to a dispute over the succession of leadership in the Muslim community following the death of the Prophet Muhammad in 632. While the two groups agree on some core tenets of Islam, there are differences in beliefs and practices, and in some cases Sunnis do not consider Shias to be Muslims.

With the exception of a few countries, including Iran (which is majority Shia) as well as Iraq and Lebanon (which are split), most nations with a large number of Muslims have more Sunnis than Shias. In the U.S., 65% identify as Sunnis and 11% as Shias (with the rest identifying with neither group, including some who say they are “just a Muslim”).

How do Americans and Europeans perceive Muslims?

A Pew Research Center survey conducted in 2014 asked Americans to rate members of eight religious groups on a “feeling thermometer” from 0 to 100, where 0 reflects the coldest, most negative possible rating and 100 the warmest, most positive rating. Overall, Americans rated Muslims rather coolly – an average of 40, which was comparable to the average rating they gave atheists (41). Americans view the six other religious groups mentioned in the survey (Jews, Catholics, evangelical Christians, Buddhists, Hindus and Mormons) more warmly.

Republicans and those who lean toward the Republican Party gave Muslims an average rating of 33, considerably cooler than Democrats’ rating toward Muslims (47). Republicans also are more likely than Democrats to say they are very concerned about the rise of Islamic extremism in the world and to say that Islam is more likely than other religions to encourage violence among its believers.

In spring 2015, we asked residents of some European countries a different question – whether they view Muslims favorably or unfavorably. Perceptions at that time varied across European nations, from a largely favorable view in France (76%) and the United Kingdom (72%) to a less favorable view in Italy (31%) and Poland (30%).

How do Muslims and Westerners perceive each other?

In a 2011 survey, majorities of respondents in a few Western European countries, including 62% in France and 61% in Germany, said that relations between Muslims and Westerners were bad, while about half of Americans (48%) agreed. Similarly, most Muslims in several Muslim-majority nations – including Turkey, Lebanon, Egypt and Jordan – agreed that relations were bad, although fewer Muslims in Pakistan (45%) and Indonesia (41%) had this view.

The same survey also asked about characteristics the two groups may associate with one another. Across the seven Muslim-majority countries and territories surveyed, a median of 68% of Muslims said they view Westerners as selfish. Considerable shares also called Westerners other negative adjectives, including violent (median of 66%), greedy (64%) and immoral (61%), while fewer attributed positive characteristics like “respectful of women” (44%), honest (33%) and tolerant (31%) to Westerners.

Westerners’ views of Muslims were more mixed. A median of 50% across four Western European countries, the U.S. and Russia called Muslims violent and a median of 58% called them “fanatical,” but fewer used negative words like greedy, immoral or selfish. A median of just 22% of Westerners said Muslims are respectful of women, but far more said Muslims are honest (median of 51%) and generous (41%).

One of the unfortunate results of the politicization of immigration in America is that it overshadows the true contribution that the Hispanic community makes in this country. It causes certain Americans to look upon our community with suspicion when - in fact - our community isn’t changing America for ill, but reminding America of who she once was.

One of the unfortunate results of the politicization of immigration in America is that it overshadows the true contribution that the Hispanic community makes in this country. It causes certain Americans to look upon our community with suspicion when - in fact - our community isn’t changing America for ill, but reminding America of who she once was. There were 1.6 billion Muslims in the world as of 2010 – roughly 23% of the global population – according to a Pew Research Center estimate. But while Islam is currently the world’s second-largest religion (after Christianity), it is the fastest-growing major religion. Indeed, if current demographic trends continue, the number of Muslims is expected to exceed the number of Christians by the end of this century.

There were 1.6 billion Muslims in the world as of 2010 – roughly 23% of the global population – according to a Pew Research Center estimate. But while Islam is currently the world’s second-largest religion (after Christianity), it is the fastest-growing major religion. Indeed, if current demographic trends continue, the number of Muslims is expected to exceed the number of Christians by the end of this century. There are two major factors behind the rapid projected growth of Islam, and both involve simple demographics. For one, Muslims have more children than members of other religious groups. Around the world, each Muslim woman has an average of 3.1 children, compared with 2.3 for all other groups combined.

There are two major factors behind the rapid projected growth of Islam, and both involve simple demographics. For one, Muslims have more children than members of other religious groups. Around the world, each Muslim woman has an average of 3.1 children, compared with 2.3 for all other groups combined.