Pónle Acento, Spanish for “put the accent on it.” Sponsored by Major League Baseball and spearheaded by Los Angeles Dodgers first baseman Adrián González. It recognizes the influence of the game’s Latino players.

Shortstop Eduardo Núñez was sitting in the locker room at Major League Baseball’s All-Star Game last month when a clubhouse employee walked in. The man was holding Núñez’s jersey but calling out an unfamiliar name. It sounded like “Noonez.”

Beside Núñez was Seattle Mariners second baseman Robinson Canó, a fellow Dominican. He shared a tip: There was a new campaign, Canó explained, called Ponle Acento — Spanish for “put the accent on it.” Sponsored by Major League Baseball and spearheaded by Los Angeles Dodgers first baseman Adrián González, it’s an effort to recognize the influence of the game’s Latino contingent by putting accent marks on the names on players’ jerseys.

Núñez, who was recently traded to the San Francisco Giants, requested a tilde after the Yankees traded him to the Minnesota Twins in 2014, but it took a few games to materialize. (Yankees uniforms do not have names on them.) The “ñ” finally came, but Núñez stopped short of asking for the acute accent that is also in his name. First things first, he reasoned: No more “Noonez.”

(The New York Times has not generally rendered accents for the names of coaches and players in daily coverage of the major North American sports leagues.)

Eduardo Núñez, now a Giants shortstop, had a tilde on his Twins jersey but stopped short of asking for an acute accent on the “u.” Credit Hannah Foslien/Getty Images

The Ponle Acento campaign is meant to remind teams to ask their players how they want their names rendered. Núñez joined the league’s broader Spanish-language media push after talking to Canó, making him one of more than 20 players, representing at least 10 teams, to become involved since it began in May. “Our names represent our families and where we come from,” Núñez said.

There are more than 200 players from Spanish-speaking countries in Major League Baseball, making up about 25 percent of the league. Of course, not all of them have names that require accents. González, who was born in San Diego but spent his early childhood in Mexico, embraced the cause by posting photos of his newly accented jersey on Twitter and challenging his teammates to join. The utility player Enrique Hernández, a Puerto Rican, immediately followed suit.

“Look how pretty ‘Hernández’ looks with its accent,” he wrote on Instagram. “Now I invite all my Latino brothers to get their accent.”

Advertisement

Continue reading the main story

To the untrained ear, González might seem an unlikely champion of the initiative. Without the accent mark, his own last name is bruised but not botched, though a Spanish grammarian would call it misspelled.

In the past, teams responded on an ad hoc basis to spelling requests, but they rarely sought out players to ask their preferences, and most players, taking the cue, had a lax attitude about the issue. As the demographics of the game changed in recent years, however, players began to be more vocal, and front offices became more proactive. “I became accustomed to not having the accent on my uniform, but now I’m embracing the opportunity,” said Yoenis Céspedes, the Mets outfielder.

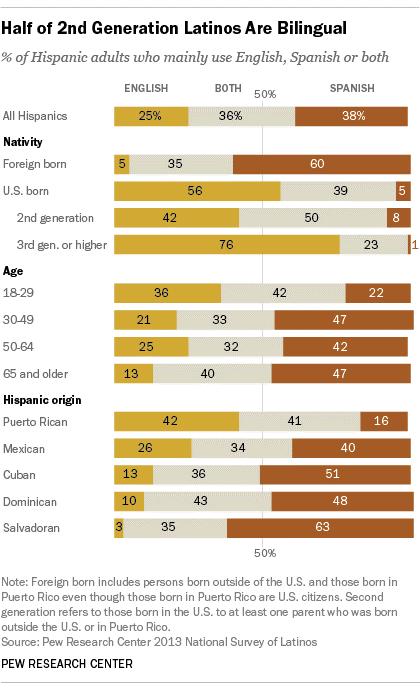

In 2015, baseball started a Spanish-language outreach campaign called Aquí, with commercials featuring stars like Miguel Cabrera, José Bautista and David Ortiz. One string of images contrasted Canó’s jersey before and after it had the accent mark. The message was clear: The game was adapting to the new wave of players who were helping redefine it.

Latino players have shown great forbearance in dealing with the inevitable mishandling of their names in the United States. But the history of linguistic confusion has followed a more insidious pattern. For years, players like Roberto Clemente or Orestes Miñoso, who was known as Minnie, were quoted in the press in broken English, with reporters exaggerating their malapropisms and mispronunciations. Clemente was quoted as feeling “no gud” when he was injured, Miñoso as being “hokay.”

The Cuban player and coach Miguel Ángel González was dogged by the nickname “the smart dummy” in the American press because of his limited English. “The man had a great baseball mind, but when it came to quoting him, the papers represented his words phonetically,” said the historian Adrian Burgos Jr. of the University of Illinois. “There was always a focus on how players spoke, not on what they said. People have seen Major League Baseball as a creator of Americanization rather than a source of diversity.”

American fans may not have known it, but some of their favorite players went by different names while they played. In the 1960s, the Giants outfield was filled — at one point simultaneously — by three Dominican brothers: Felipe, Mateo and Jesús Alou. Their full last name was Rojas Alou, but, inexplicably, Rojas was lopped off early in their careers, most likely by a scout, never to be restored. (Felipe’s son, who entered the majors in 1990, went by Alou as well.)

The record books are littered with similar truncations, misspellings and flip embellishments. In his book “The Pride of Havana,” the Yale scholar Roberto González Echevarría mentions the case of the Cuban infielder Hiraldo Sablón Ruiz. In Cuba he was known as Hiraldo Sablón, but in the United States, where he played for the Reds and the Angels, his name contracted to Chico Ruiz. Calling a player Chico, González Echeverría wrote, “would be like calling the Yankee star ‘Buddy’ Mantle because someone said, ‘Way to go, buddy!’ when he hit a homer.”

Notice anything different? Robinson Canó as an All-Star in 2014, left, and as one in 2016, right.

Matt Vasgersian, MLB Network’s studio host and play-by-play announcer, is trying to correct for the news media’s long history of glaring errors. He gave the example of the Venezuelan Hernán Pérez, which he pronounced both with and without the accents, for effect. “It sounds almost like two different guys,” he said.

Vasgersian does not speak Spanish, but he grasped the full force of the contrast. As Burgos said, citing the famous Duke basketball coach, “If you can say Krzyzewski, then you can say Rodríguez.”

One of the few Latino baseball commentators these days is Carlos Peña, who played first base for 14 seasons before moving to the broadcast booth.

“Some words mean something else when you don’t pronounce them right,” he said. Stripped of its accent mark, Bartolo Colón’s surname is not Spanish for Columbus; it becomes the name of a part of the large intestine. Stripped of its tilde, peña, which means rock, becomes pena, which is Spanish for pity or pain. When Peña played in the minor leagues, where clubs did not have the resources to hire in-house tailors to render players’ names correctly on their jerseys, he said, he used to put the accent mark on his uniform himself, with a piece of athletic tape.

Recently, his 5-year-old son began playing in a youth baseball league. When he came home the other day with his team jersey, Peña was dismayed to find the tilde missing.

“It bothered me more that it happened to my son than if it had happened to me,” he said.

Your Editor Exclaims:

Terrific. The tilde on the eñe and the accent on García.

I am